Benefits of Hydro

Because it relies on the water cycle, a naturally replenishing source, hydroelectric dams generate energy as long as there is rainfall and rivers continue to flow.

Hydroelectric generated electricity is a carbon-free generation resource that help reducing the overall carbon footprint of the energy sector.

How Hydro Works

Flowing water referred to as hydropower is the most widely used renewable energy source in the world.

Hydropower generates less pollution than fuel-burning power generation methods and creates public recreational areas and new habitats for wildlife.

A waterway is dammed to create a water reservoir.

The water from the reservoir is released.

The force of the water turns the turbine.

The turbine turns a generator creating electricity.

Our Hydro Plants

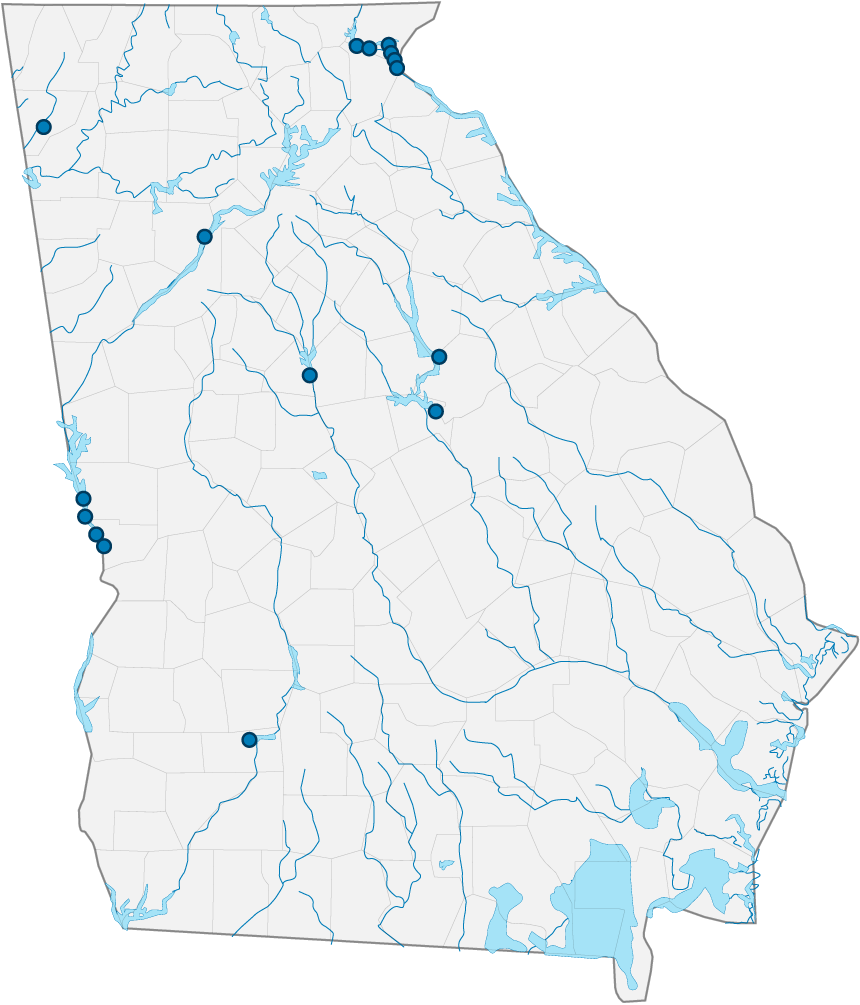

Our 15 hydroelectric generating plants are distributed across the state in three groups: the North Georgia Hydro Group, the Chattahoochee Hydro Group, and the Central Georgia Hydro Group.

1. North Georgia Hydro Group

Burton |

8.1 MW |

Nacoochee |

5.5 MW |

Terrora |

20.8 MW |

Tallulah Falls |

72 MW |

Tugalo |

58 MW |

Yonah |

22.5 MW |

2. Chattahoochee Hydro Group

Morgan Falls |

16.8 MW |

Bartletts Ferry |

187.1 MW |

Flint River |

5.4 MW |

Goat Rock |

40.5 MW |

North Highlands |

29.6 MW |

Oliver |

60.1 MW |

3. Central Georgia Hydro Group

Lloyd Shoals |

18 MW |

Sinclair |

45 MW |

Wallace |

321.3 MW |

4. Co-Owned

Rocky Mountain |

229.4 MW |

Georgia Power: 25.4%

Oglethorpe Power Corporation: 74.6%

North Georgia Hydro Group

| Burton | 8.1 MW |

| Nacoochee | 5.5 MW |

| Terrora | 20.8 MW |

| Tallulah Falls | 72 MW |

| Tugalo | 58 MW |

| Yonah | 22.5 MW |

Chattahoochee Hydro Group

| Bartletts Ferry | 187.1 MW |

| Flint River | 5.4 MW |

| Goat Rock | 40.5 MW |

| North Highlands | 29.6 MW |

| Oliver | 60.1 MW |

Central Georgia Hydro Group

| Lloyd Shoals | 18 MW |

| Sinclair | 45 MW |

| Wallace | 321.3 MW |

Morgan Falls Hydro Project

| Morgan Falls | 16.8 MW |

Co-Owned

| Rocky Mountain | 229.4 MW |

Georgia Power: 25.4%

Oglethorpe Power Corporation: 74.6%

Enjoy Our Lakes

While operating our hydroelectric dams, we are also the largest non-governmental provider of recreation facilities in Georgia, managing the over 100,000 acres of the land surrounding our beautiful lakes and rivers.

Our lakes, rivers and parks are perfect for swimming, hiking, camping, fishing, hunting, and more!

Bartlett's Ferry Dam Circa 1930

When Georgia Power began upgrading the spillway gate system at Bartletts Ferry Dam in 2018, it was determined that the original gantry cranes, which had been in place since the dam’s completion in 1925, would have to be replaced. This initiated consultation with the Georgia and Alabama State Historic Preservation Officers (SHPO), as well as the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC). Since the cranes could not be preserved in place, extensive archival documentation in the Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) was conducted prior to their removal.

Ongoing FERC Licensing Proceedings

Langdale and Riverview Projects’ License Surrender

Georgia Power is proposing to decommission the Langdale and Riverview Projects and remove Langdale Dam, Crowhop Dam, Riverview Dam and the Riverview Project powerhouse.

Cultural and Historic Resources

Frequently Asked Questions

How many different types of hydropower are there?

The term “hydropower” covers a wide variety of technologies, ranging from large to small and old to new. Most commonly associated with the term are dams, which store water behind a generating facility and harness its power through one of many different types of turbines. This type of conventional hydropower project represents the vast majority of U.S. hydropower generation. New technologies have entered the market or seen major advances in recent years, including ocean wave, tidal and hydrokinetic power (tapping the power of flowing water, much like wind power does with moving air).

Does hydropower help to combat climate change?

Yes. Unlike power plants that burn fuels like coal, oil or gas, hydropower plants do not emit climate-altering gases that contribute to the greenhouse effect. If we take into account the complete life cycle of a hydropower plant, the quantity of CO2 produced per kilowatt-hour of energy generated is between 35 and 70 times lower than the amount produced in energy production using fossil.

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), 4,333 terawatt-hours of hydroelectric energy were produced worldwide in 2019, saving more than 2 billion metric tons of CO2 a year – not to mention the benefit of reduced water consumption compared with fossil fuel-powered plants, which use enormous volumes of water for cooling purposes.

Does hydropower help rural economies?

For centuries, since its initial use to drive watermills, the power of water has been harnessed to benefit communities’ development. Both the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) and the World Bank continue to recognize and reaffirm the role of hydropower in the development of local and rural economies. In the case of large plants, the benefits also include the creation of jobs, while all hydropower facilities provide an abundant source of power that is adaptable to local energy needs, enabling communities to move closer to energy self-sufficiency. Small plants, suitable for more remote areas or less industrialized contexts, are a fundamental opportunity to support local economic growth.

What is the average lifespan of a hydropower plant?

In the case of hydropower plants, we rarely talk about the total dismantling of a facility, but rather about a modernization of structures such as dams and pipelines. The elements that need to be changed most often are the hydraulic turbines that operate as generators, transforming the power of water into electricity. The lifespans of these turbines range from 40 to 80 years, but sometimes they can be replaced earlier if new, more efficient technologies become available. Some large hydropower plants have already been running for more than 120 years and are still fully operational. In other cases, however, climate change – with the increasing frequency and severity of droughts or the reduction in available water it can bring – has led to the closure of plants.

Is hydropower cost-effective?

The power of water is present everywhere on Earth and the transformation of this power into electric energy has already achieved extraordinary performance levels, with efficiency in excess of 80%. Thanks to technological innovations and digitalization, the quantity of energy wasted is being further reduced. While the initial investment to create a power plant can be quite high, overall, hydropower is the cheapest in the medium and long term.

Do hydropower plants have an impact on the environment?

Hydropower plants pose questions concerning sustainability for the environment, the landscape, fish populations and the balance of ecosystems. Even before the focus shifted to improving efficiency, the emphasis was on reducing all types of impact on the environment and on finding strategies to harness the power of water without damaging the wildlife that live in or depend on it.

The management of reservoirs can actually mitigate the effects of adverse climate events, encourage the growth of vegetation and crops and, at opportune times, the water can be made to flow in such a way as to ensure the integrity of the natural biological context and the passage of fish, using so-called Minimal Vital Flow (MVF) technology, or fish ladders that enable fish to follow the current of a river both upstream and downstream.

Have questions regarding Georgia Power Lakes?

Get answers to some frequently asked questions regarding Georgia Power lakes.